While some schools and LinkedIn advisors continue to sell magic prompts for engagement, the age of prompting domination is fading. Context engineering is setting the stage, and this discipline teaches us to build the words machines think within.

In scientific language, context engineering can be defined as the systematic design and management of the information an AI model encounters before generating an answer. In practical terms, it means that the focus nowadays shifts from refining how we ask questions to engineering what data and context the model can access when producing a response.

Why is this shift happening? It’s simple. Context engineering enables more accurate and predictable results beyond the tricks of wording. With this technique, the right information, tools, and context define the success of your AI project from the start. This is the most valuable for business, isn’t it?

From prompts to environments

What prompt engineering got us

Prompt engineering, or the craft of writing and structuring instructions for an LLM, got us surprisingly far. It’s quick to implement and iterate, requires no model training, and enables rapid prototyping of AI capabilities. With a bit of ingenuity, almost anyone could tweak a prompt to improve an answer, making prompt engineering a low-barrier, high-agility technique for initial AI experiments.

This approach excels in straightforward, stateless tasks — such as composing a single email or generating a short story — where you simply outline the task, perhaps provide a few examples, and the model delivers a relevant response. Its strengths lie in speed, flexibility, and minimal setup, making it ideal for one-off interactions and early-stage demonstrations.

But prompt-only methods hit limits as we asked AI to do more. Beyond neat tricks and one-shot outputs, prompt tweaks alone couldn’t handle complex workflows. Prompt engineering, while still necessary, becomes insufficient for applications that require memory, multi-step reasoning, or real-time knowledge.

What context engineering changes

If prompt engineering is about crafting how you ask, context engineering is about designing what the model sees. It focuses on deciding what information the model should consume, how that information is selected and structured, and how it’s refreshed over time. Crucially, context engineering expands the canvas from a single prompt string (remember our article about How Models Search and Act) to the entire environment of data available to the model at inference. This includes things like the user’s profile and preferences, conversation history, retrieved documents or knowledge, relevant database records, available tools or APIs the AI can call, and governance policies or guardrails on its behavior. In short, it’s about equipping your model with facts, memory, capabilities, and constraints.

Where prompt engineering might treat each query in isolation, context engineering treats context as an evolving, dynamic input. The data fed to the model can change based on the user’s past interactions, the latest external information, or the system’s state.

For example, rather than hoping a prompt “Please answer with current stock prices” will work, a context-driven system would call an API to get those prices and feed them into the model. Rather than a static one-shot question, modern AI systems assemble context on the fly – pulling in conversation logs, database results, and API outputs – so that the model is always grounded in up-to-date, relevant information. In practice, context engineering means building pipelines that pre-load the model’s “working memory” with exactly the right content before each query.

This shifts the emphasis from prompt eloquence to information architecture. We are no longer just writing instructions; we are architecting an information flow that surrounds each model call.

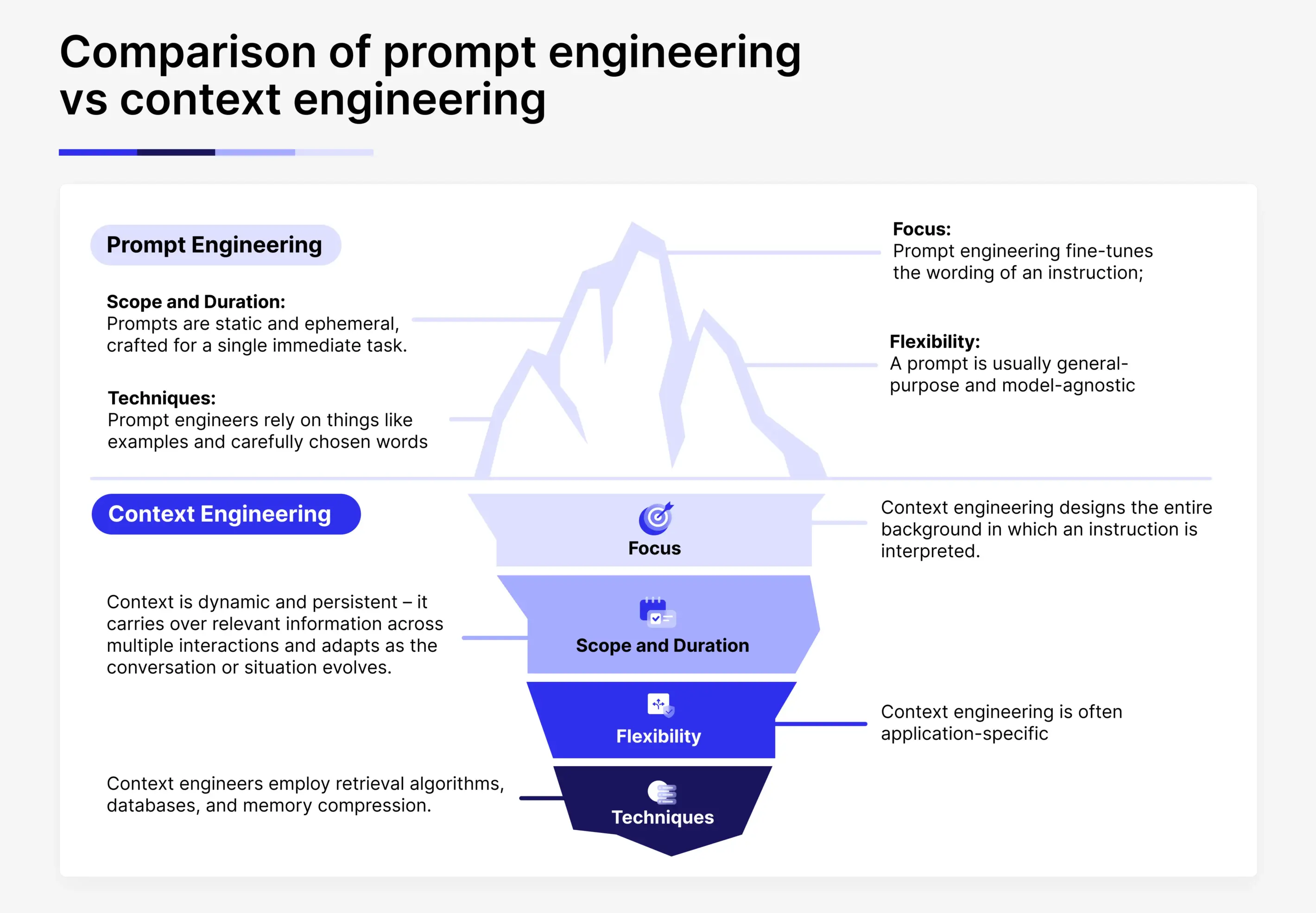

Context engineering vs prompt engineering

Sombra’s architects like to emphasize that prompts are the tip of the iceberg; context is everything beneath the surface. To clarify this distinction, consider a few points of comparison between prompt-focused and context-focused approaches:

- Focus: Prompt engineering fine-tunes the wording of an instruction; context engineering designs the entire background in which an instruction is interpreted. One is about the sentence you send, the other about the data and state the model has access to when reading that sentence.

- Scope and Duration: Prompts are static and ephemeral, crafted for a single immediate task. In contrast, context is dynamic and persistent — it carries over relevant information across multiple interactions and adapts as the conversation or situation evolves.

- Flexibility: A prompt is usually general-purpose and model-agnostic (you hope any GPT-4 will understand it), whereas context engineering is often application-specific —tailored schemas, memory structures, and data retrieval tuned for your domain.

- Techniques: Prompt engineers rely on things like examples and carefully chosen words (e.g., “Explain step-by-step”). Context engineers employ retrieval algorithms, databases, and memory compression. For instance, instead of a long prompt with all instructions, you might design a system where the model always sees a role definition, the latest user data, relevant documents, and tool outputs as separate components each time.

Put simply, prompt engineering tweaks the query, while context engineering builds the knowledge base and scaffolding that make the query answerable. This broader approach turns the AI from a clever respondent into something closer to an informed problem-solver.

Synergy instead of replacement

Importantly, context engineering isn’t a replacement for prompt engineering so much as an evolution of it. The two work in tandem. You still need to tell the model what you want (that’s the prompt part), but, as we said before, you also ensure the model has the knowledge and tools to fulfill the request (that’s the context part). The best systems use both: they feed the model rich context and use carefully designed prompts to guide the model’s reasoning or style.

In a complex task, your prompt might establish the question and desired format (“Explain the cause of the outage in bullet points, citing logs”), while the context gives the raw materials (the relevant log lines, metrics, etc.). If you only had the prompt, the answer might be well-structured nonsense. If you only had the context with no instruction, the model might not know what to do with it. Together, you get factual, formatted results.

Research and practice have also shown interesting synergies: for example, combining retrieval (context) with chain-of-thought prompting can yield excellent analytical performance. The retrieved data grounds the model, and the prompt’s chain-of-thought instruction encourages it to reason step-by-step with that data. Neither technique alone might solve a tricky problem, but together they can. This mirrors a trend in ML where different techniques complement each other rather than strictly supplanting each other.

In some cases, we can even say that “context engineering is the new prompt engineering,”

The benefits of context engineering

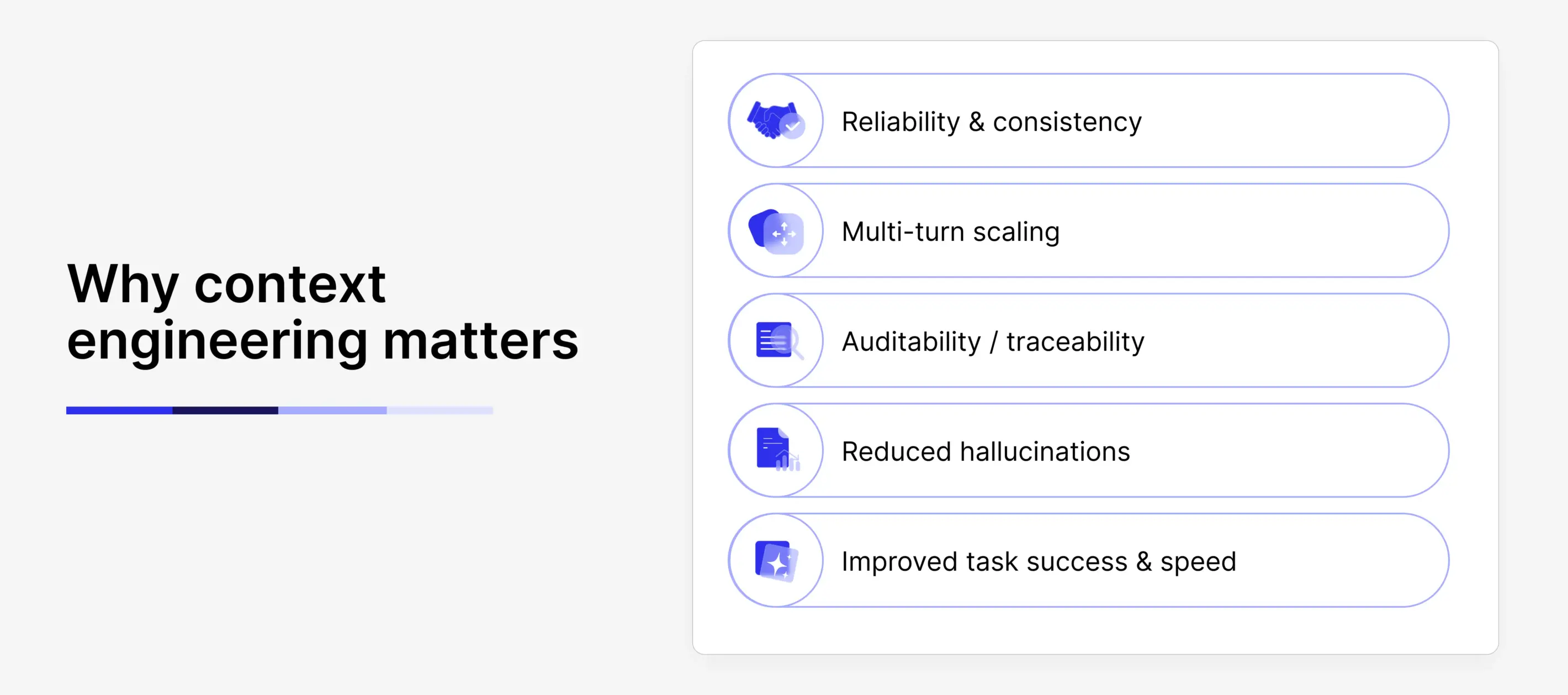

Making AI models reliable and consistent

One of the driving forces behind the move to context pipelines is reliability. By grounding model outputs in retrieved, structured data rather than model guesswork, context engineering markedly reduces hallucinations and errors.

When an LLM has the relevant document snippet or database record in its context window, it doesn’t have to fabricate an answer – it can quote or reason over the real data. In the realm of observability (AI for IT operations), practitioners found that “without proper context, AI ends up summarizing symptoms instead of explaining causes. In contrast, when the AI is fed rich logs and metrics as context, it can diagnose the root issue, not just regurgitate generic advice.

Overall, teams report that treating context as part of the system architecture yields far more consistent and repeatable behavior from models. Ad hoc prompting often produced flaky results – the model might give a great answer one minute and a nonsensical one the next, based on subtle wording changes. Context engineering stabilizes this by standardizing what the model sees.

Scaling beyond single use-cases

The importance of context engineering becomes even more apparent when scaling AI across complex use cases. Enterprises need AI systems that work across many users and many interactions, not just a single Q&A exchange. They need AI that can handle multi-turn dialogues, multi-user environments, compliance rules, and audit requirements. Prompt engineering alone doesn’t offer mechanisms for these needs – but context engineering does.

For example, in enterprise applications it’s critical to have an audit trail of what information influenced each AI decision. Context pipelines allow exactly that: engineers can log which documents were retrieved, or which profile data was injected into the model for a given answer. This means when an AI makes a recommendation, you can trace it back (“it cited in Article 5 of Policy X, pulled from the knowledge base”). Such governance is impossible if all you have is a monolithic prompt that can’t be easily dissected. Versioning and governing context have become the best practice. As experts advise, we should “treat context as infrastructure, not a prompt file” – standardize context assembly pipelines with proper data curation, privacy controls, and logs of what tokens went into each answer.

Another reason context engineering is winning is the scalability to more complex tasks. Early on, using LLMs was like having a very smart answer box – useful for a single question, but not integrated into larger workflows. Now, with context engineering, AI can become a reliable system component. This means that AI assistants that previously just answered generic questions now can plug into your logging tools, ingest real metrics, follow escalation policies, and actually solve problems.

Actual use cases for context engineering

AI agents that don’t forget

Consider the emerging class of AI agents – systems that perform sequences of actions autonomously. Prompt engineering might handle the initial instruction to such an agent, but it’s context engineering that keeps the agent effective over time. In these systems, context goes well beyond the latest user message. It includes things like tool access definitions, the agent’s prior actions and results, the current system state, and overarching policies or goals.

For instance, a DevOps chatbot could have access to a deployment tool and a monitoring API. Rather than expecting a single prompt to manage everything, we’d engineer context so that with each step, the agent sees a summary of what it’s already tried, the outputs of any tool calls (like the log from a diagnostic command), and any persistent goals (“ensure zero downtime”) or constraints (“don’t reboot without approval”).

This way, the agent doesn’t forget what it did two steps ago and doesn’t violate policies.

Paul Lopez, a development veteran, describes this shift for sophisticated agents: as we move to multi-turn agentic systems with tools and memory, “prompt engineering has evolved into context engineering. Modern systems must manage access to multiple tools, internal knowledge bases, domain knowledge, system instructions, and even memory — all of which feed into the agent’s context.”

In practice, this means when an agent uses a tool and gets a result, that result is immediately fed into its context for the next reasoning step — and irrelevant data is pruned away to avoid clogging the context window. The agent’s “mind” at any moment is the sum of the carefully chosen context items we’ve given it: recent tool outputs, critical system facts, and the current objective. At Sombra, we agree with this statement.

The payoff is huge. AI agents engineered with rich context can tackle long-lived tasks that were impossible with prompts alone. They maintain state over hours or days, coordinate sub-tasks, and adapt to new information on the fly. A prompt-only agent, by contrast, tends to either forget earlier instructions or get irretrievably confused (“Whoops, I already did that!”) because there’s no memory. Context engineering keeps the long-term state.

Root cause analysis with context

A good example of context engineering is AI-driven root cause analysis for software incidents. In practice, incidents rarely arrive as neat datasets. And a simple prompt like “Here are the logs – what caused the outage?” often fails because the model sees noise instead of a story.

Effective RCA is about connecting those fragments. Logs show what broke, metrics show how the system behaved, traces show where the request path failed, and deployment or configuration changes show what might have triggered the shift. A context-engineered system mirrors how an engineer thinks: it gathers the relevant pieces from each source, lines them up around the moment of failure, and presents them as a focused, structured view.

That shift changes the quality of the answer. Without context, the model stays cautious and generic: “check the network.” With a narrative of evidence – a database error at 3:45 PM, a sudden CPU spike, and a deployment minutes earlier – it can follow the chain of events and explain what actually happened: a database deadlock exhausted the API thread pool and brought the service down.

In that sense, context engineering gives the model a timeline plus the data. It turns isolated symptoms into a sequence of causes and effects, allowing the AI to reason through an incident the way a human investigator would.

Enterprise assistants and memory

Another line of case studies points to a quieter shift inside large organizations: the emergence of enterprise assistants that carry context forward over time. These systems are designed to behave like colleagues who build on prior work across projects and weeks, guided by accumulated knowledge rather than isolated sessions.

Consider a design team using an AI assistant for internal copy. In January, a product manager revises a draft and notes a preference for a more informal tone. That preference is stored as part of the user’s working profile. Months later, when the same manager asks for a new draft, the system brings that detail back into the model’s context. The writing arrives already aligned with the person who requested it.

Over time, these systems gather more than stylistic notes. They collect decisions from past projects, patterns in how teams resolve issues, and pieces of institutional memory that often live in shared documents or meeting notes. A meeting assistant, for example, can surface last week’s action items at the start of a new agenda because those notes are retrieved and placed into the model’s working context.

The effect is a change in how the assistant participates in daily work. It can say, “Based on what you chose before, here is what I’ve prepared now.” For users, this feels like collaboration: the AI operates within an ongoing process, guided by accumulated context.

How to actually do context engineering

From this point, the idea of context engineering usually feels clear in theory. The harder question is what it looks like once you sit down to build it. Most teams don’t start with an architecture diagram or a formal “context layer.”

They start with a problem: an AI that gives answers that sound right yet misses the details that matter. The shift happens when you stop asking how to phrase a better prompt and start asking how to make the right information reliably show up in front of the model at the right moment. That practical mindset – treating context as something you design, store, and deliver – is where implementation begins.

Core building blocks

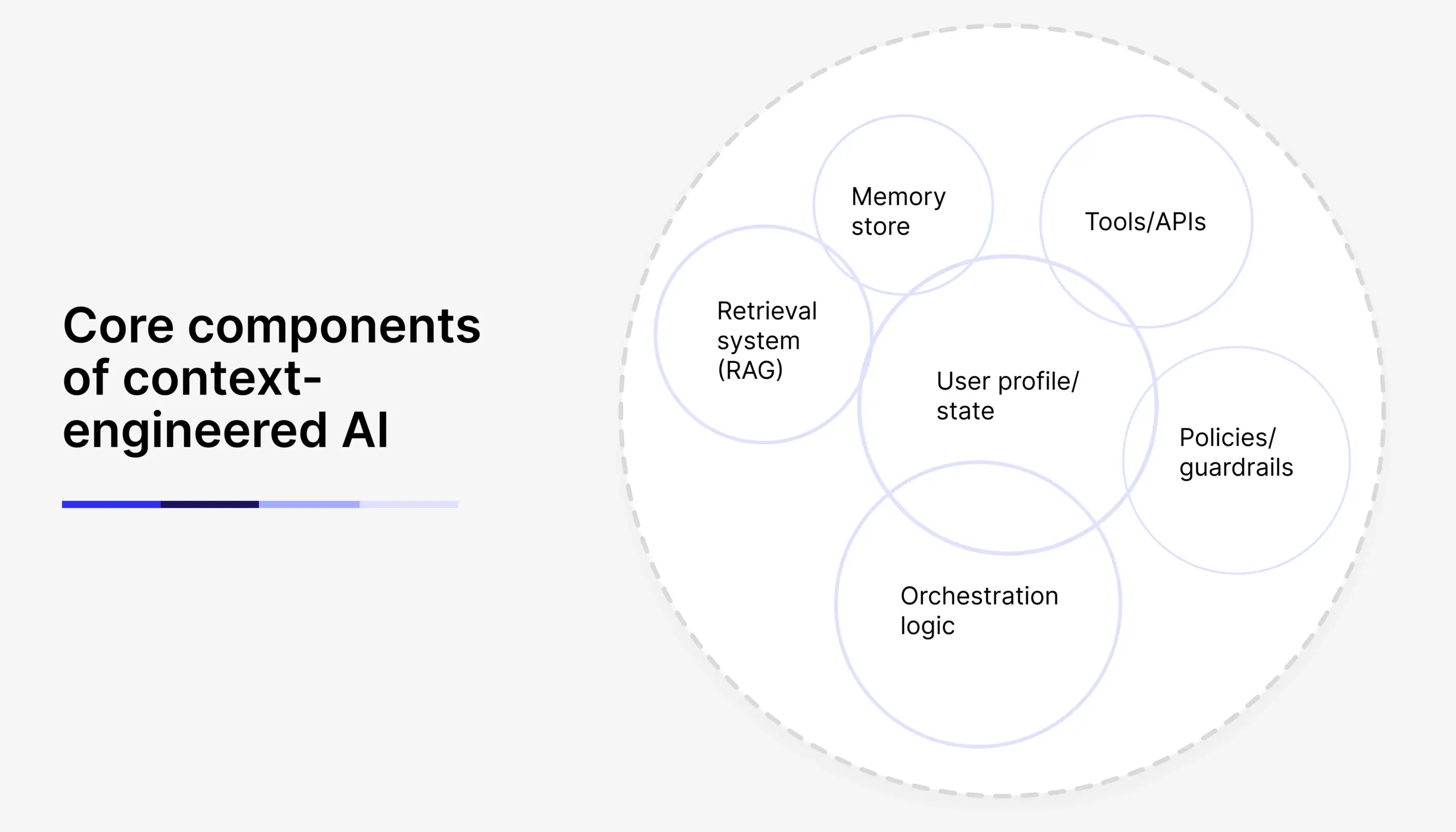

Context engineering is largely… an engineering problem, i.e., the right data pipelines, architecture around the model, and design of a backend system. So, the core components of a context-engineered application typically include:

- Retrieval system (RAG): A knowledge base or document store plus an embeddings index and search retriever. This lets the system pull in relevant facts or documents on the fly. For example, a vector database of company documents that can be queried with the user’s question to fetch background context.

- Memory store: Some way to persist in conversation history or user-specific data beyond a single turn. This could be as simple as a database table or as complex as a specialized memory service. Short-term memory might store the last N interactions; long-term memory might store summaries or key preferences learned about the user.

- User profile / state: Related to memory, this stores persistent attributes about the user or session (roles, permissions, preferences, past actions).

- Tools / APIs: Integrations that allow the AI to take action or fetch data. Each tool comes with a definition or schema (for example, what inputs it accepts) that is part of the context given to the model. A classic example is a calculator tool – rather than prompting the model to do math, you give it a tool and include in context: “You can call a calculator function for arithmetic.”

- Policies / guardrails: Constraints and rules embedded in the context. These often live in the system prompt or a policy module (e.g. “If the user asks for medical advice, respond with a disclaimer”). They act as a safety net by embedding rules directly into the context environment.

- Orchestration logic: The glue that assembles the context for each interaction. Often implemented as an orchestrator script or framework, this component pulls the latest user input, fetches relevant data via the retriever, grabs any needed memory or profile info, and combines it all (usually in a structured prompt format) for the mode. The orchestrator also might handle multi-step reasoning, calling the model multiple times (e.g., first to summarize recent history, then to answer using that summary).

Sounds massive, but teams can start small. A minimal context stack that you could implement might include: (a) a simple document or FAQ repository with an embedding-based search (to provide knowledge retrieval); (b) a basic user context store (even a JSON file or database table recording past interactions or user settings); and (c) an orchestration layer that takes the user’s query, fetches the top relevant docs from (a) and any profile info from (b), and inserts them into a pre-defined prompt template (system message + context + user question).

Even this basic setup – essentially, a Retrieval-Augmented Generation loop with a bit of memory – can dramatically improve an AI’s usefulness over prompt-only behavior. It ensures the model isn’t operating in a vacuum but has some grounding in real data and past context each time it responds.

The key takeaway is that context engineering mostly leverages existing technologies (search, databases, APIs) arranged in the right way for AI. By focusing on these building blocks, teams can build systems where the heavy lifting is done by the data pipeline – and the model just has to do what it’s best at (reasoning and language) with the right information in hand.

Starting with layered context architecture

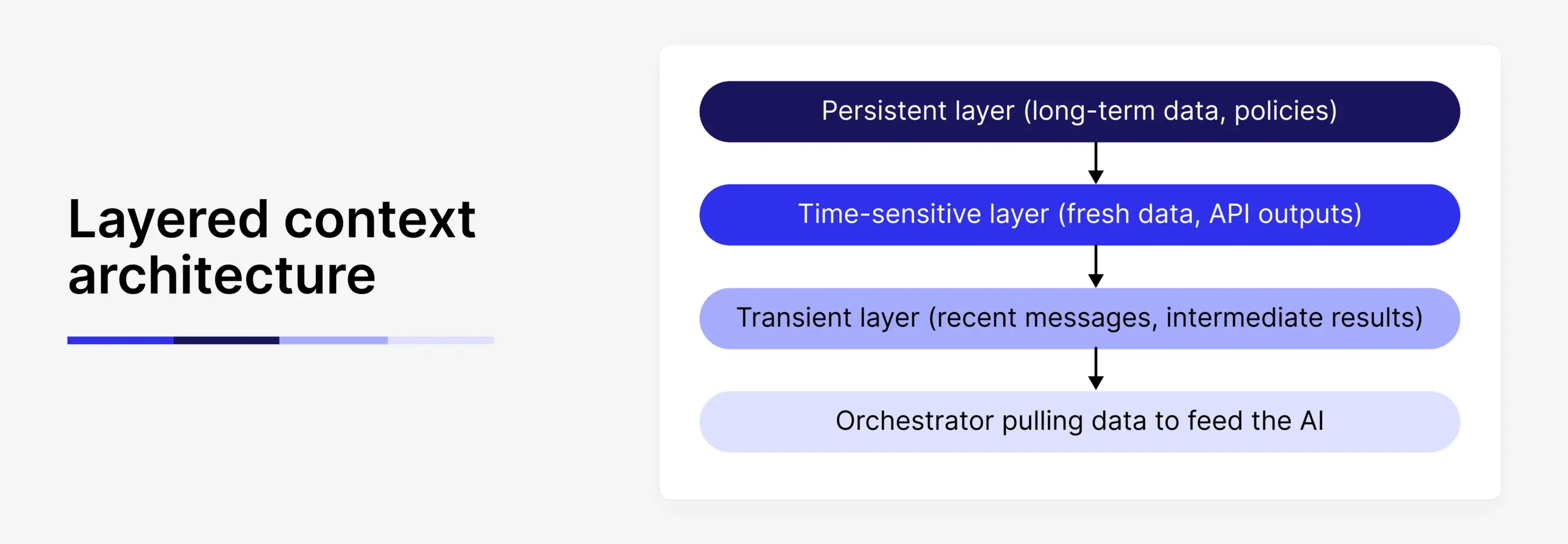

Once the core building blocks are in place, the next step is deciding how they come together at runtime. Most production systems do this through a layered context architecture. The idea is simple: different kinds of information change at different speeds and treating them as a single block makes systems harder to reason about, debug, and evolve.

At the foundation sits a persistent layer. This holds information that defines identity and behavior over long periods of time: who the user is, what role the system is playing, and which policies or constraints apply. It rarely changes during a session, and often only changes when a user’s permissions, preferences, or organizational rules are updated. This layer gives the model a stable frame of reference for how it should behave.

Above that sits a time-sensitive layer. This is where fresh knowledge enters the system: documents retrieved from a database, records returned by an API, or facts pulled from an internal service at the moment of the request. This layer is rebuilt on every interaction. Its purpose is to ensure the model is reasoning over current, relevant information rather than relying on assumptions or outdated training data.

At the top is the transient layer. This is the working memory of the interaction: the last few user messages, the model’s most recent responses, and any intermediate results produced by tools. It changes from turn to turn and gives continuity to the task at hand.

Each request triggers an assembly process. The orchestrator pulls a stable identity and policy frame from the persistent layer, injects fresh data from the time-sensitive layer, and adds the recent interaction state from the transient layer. The model receives a composite view that reflects who it is supposed to be, what it needs to know right now, and what has just happened in the conversation.

This structure turns context into something closer to an interface than a static prompt. Business rules, live data, and user history are not implied through careful wording. They are supplied explicitly as part of the system’s input. That shift makes behavior easier to control and outcomes easier to explain, because each response can be traced back to the specific pieces of context that shaped it.

Effective context for AI agents

When systems move from single-turn interactions to long-running agents, context management becomes an ongoing process rather than a one-time assembly step. The challenge is keeping the model focused as information accumulates.

One common technique is summarization and compaction. As conversations or tasks grow, earlier details are condensed into short, structured summaries. These summaries preserve decisions, variables, and goals while freeing up space in the working context. Instead of carrying a full transcript forward, the system carries a running state description that reflects what matters now.

Another pattern is external memory. Important facts, milestones, or findings are written to a store outside the model’s immediate context. This might be a simple notes file, a database table, or a dedicated memory service. When the task reaches a point where that information becomes relevant again, the orchestrator retrieves it and injects it back into the context. This allows the agent to maintain continuity over long spans of time without inflating every request.

More complex systems use multiple agents with separate contexts. One component might focus on searching and retrieving information, another — on reasoning over results, and a third on coordinating actions. Each operates within a context tailored to its role. The main controller passes only distilled outputs between them. This keeps each part of the system focused on its own responsibility and reduces the chance that irrelevant details leak into the reasoning process.

Across these patterns, the same principle applies: context is added when it becomes useful and compressed or set aside when it no longer serves the current step. The result is an agent that can sustain long workflows while staying oriented around goals, constraints, and verified information.

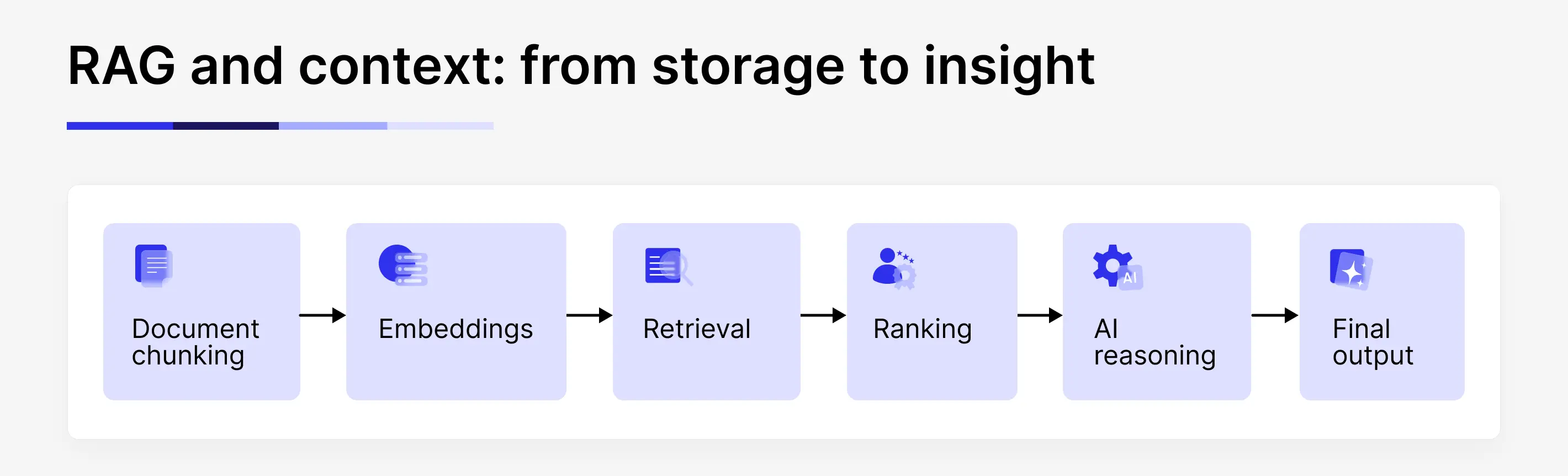

RAG and context: beyond storage

Retrieval-augmented systems often start with a simple idea: store documents in a vector database and retrieve the closest matches. In practice, the effectiveness of retrieval depends on a series of design choices that shape what the model actually sees.

Document chunking defines the unit of knowledge the system works with. Larger chunks carry more background but risk bringing in irrelevant material. Smaller chunks improve precision but can strip away necessary context. Embedding models and similarity thresholds determine what counts as “related.” Ranking and re-ranking logic decides which pieces of information earn a place in the model’s limited context window.

How retrieved content is presented also matters. Raw text, structured fields, and short summaries lead the model to reason in different ways. These choices form a pipeline, and changes in one part often ripple through the rest. Teams that treat this pipeline as a tunable system, rather than a fixed component, tend to get more reliable and predictable behavior.

Prompts continue to play an important role in this setup. Their function shifts toward guiding the model in using the retrieved information: clarifying what to prioritize, specifying answer formats, and defining rules to follow. While the substance derives from the context pipeline, the prompt directs how that substance is transformed into output.

Metrics: how to know it’s working

As context engineering becomes part of the system architecture, it also becomes something that can be measured and improved.

One set of metrics focuses on outcomes. Task success rates, resolution rates, or factual accuracy provide a direct view of whether the system is delivering useful results. Another set focuses on reliability. Consistency across repeated runs and the frequency of incorrect or unsupported answers show how well the system is grounding its responses in real data.

Operational metrics matter as well. Time to resolution indicates whether better context is speeding up workflows. Token usage and compute cost reveal whether the system is becoming more efficient or carrying unnecessary context forward.

User-facing signals often provide the clearest feedback. Ratings of helpfulness, follow-up behavior, and completion rates reflect whether the system feels aligned with the user’s needs and expectations.

To make these measurements meaningful, Sombra recommends instrumenting the context pipeline itself. You can log what was retrieved, what memory was injected, how the model responded, and what happened next. This makes it possible to compare different configurations side by side. For example, the same set of queries can be run through a prompt-only setup and through a context-augmented setup, with differences in accuracy and usefulness tracked over time.

Viewed this way, context engineering becomes an optimization process. The architecture, retrieval rules, memory strategies, and prompts are adjusted based on observed performance. Improvements show up in fewer errors, faster task completion, and smoother user experiences. The gains come from shaping how information flows into the model, rather than from changing the model itself.

Sombra case study: transforming enterprise search through context engineering

Theory outlines the intended outcomes of context engineering, while practice reveals the real-world impact. Let’s examine how the various building blocks, layers, and metrics come together in a single workflow using our case study as an example.

Our recent project was for a large enterprise company. The goal was to evolve an internal search tool from a simple keyword box into a multi-agent assistant built around a structured context pipeline.

The challenge

The client’s platform managed highly complex operational data objects, construction work orders, in particular.

A single record could contain hundreds of attributes, nested structures, internal codes, and dependencies. To retrieve insights, users relied on an advanced filter-based interface requiring deep system knowledge.

Several risks followed from that gap. Query patterns were unknown. Different teams likely searched for different kinds of information, yet the system treated every request the same. It was unclear which sources – documentation, knowledge bases, or internal data – should be present for which types of questions. The design process relied on assumptions rather than observed behavior.

They realized AI was the best tool to do both: work with the system knowledge and stay on top of their game in the market.

Our approach

Sombra shifted the focus from writing better prompts to constructing context from real usage data.

Phase 1: Context discovery through logs

Our team began by analyzing 36,000 historical search queries from the client’s logs. Clustering and categorization revealed recurring topics, common phrasing patterns, and distinct user groups. Support teams searched for error codes and troubleshooting steps. Sales teams focused on feature descriptions and pricing references. These patterns defined what the system needed to retrieve and when. Context rules were derived from behavior rather than from stakeholder guesses.

Phase 2: Multi-agent context architecture

With these patterns in place, Sombra designed a multi-agent system where each agent operated with a role-specific view of context. A central context manager maintained persistent records of user state, recent actions, and conversation threads. It formatted the context differently for each agent. Reasoning agents received structured data. Response agents received condensed summaries. Retrieval agents received search-oriented inputs. Information moved through the system in controlled handoffs, with each step preserving intent and relevant detail.

The retrieval layer was populated based on the discovered query categories. Frequently referenced FAQs, internal documentation, and advanced technical guides were embedded with metadata that aligned with user roles and query types. This allowed the system to assemble a tailored context package for each request rather than a generic bundle of documents.

Phase 3: Context-aware routing

Model and tool selection became part of the context flow. High-capability models handled complex reasoning tasks. Simpler models handled formatting and presentation when the context had already been distilled. Decisions about cost and performance were tied to how context moved between agents, rather than applied uniformly across the system.

The results

The system started automatically routing queries by category, leveraging patterns learned from original logs instead of relying on manual rules. Token usage decreased as agents received only the context relevant to their specific roles. Answers were sourced directly from retrieved enterprise data, reducing unsupported responses and building user trust. Multi-turn tasks stayed coherent because each agent inherited a structured summary of prior interactions.

Operationally, the architecture remained transparent — each agent’s inputs and outputs were logged as part of the context record, enabling traceability of response formation and data flow throughout the pipeline.

Lessons from the deployment

This project reinforced a few practical points. Effective context engineering depends on integration with real systems and real data. Logs, databases, and internal workflows define what the model should see. Collaboration with the client is essential because access to usage data shapes the entire design. Agent performance is tied to how well context is passed and transformed between components. Cost optimization follows from refining context flow, not from reducing model capability in isolation. Tool outputs and intermediate results belong in the same context pipeline as user input and retrieved documents.

Sombra’s implementation followed a repeatable pattern: discover context from behavior, design how context moves through the system, build retrieval around those patterns, optimize through measurement, and refine continuously as usage evolves.

At the center of this system sat a dedicated context manager. Its role was to preserve coherence as information moved between agents, translate formats when necessary, and ensure that each component received a view of the problem sized to its responsibility. This turned a collection of models and tools into a coordinated system.

Taken together, the case shows context engineering as an exercise in system design. The gains came from shaping how information flows — from the user to data sources, to agents, to response – rather than from changing the model itself. The outcome was an enterprise assistant that reflected how people actually work, because its context was built from their behavior and carried forward through every step of the interaction.

From clever prompts to co-intelligence

Seen through Sombra’s work, the shift from prompts to context becomes an engineering choice. The focus moves from how a question is phrased to how the environment around the model is built. Logs, documents, user roles, and live data form a context pipeline that reflects how the organization actually works.

This is where co-intelligence starts to emerge in practice. When an AI operates inside the same goals, constraints, and knowledge base as its users, its outputs align with real workflows rather than isolated requests. It can carry decisions forward and surface relevant information at the moment it matters.

Sombra’s experience demonstrates that context pipelines must be treated as core infrastructure. They are designed, versioned, and observed like any other backend system. Responses can be traced back to the specific data and rules that shaped them, making behavior inspectable and improvable.

If you’re ready to move from static prompts to deployed AI solutions, let’s build your context pipeline. Reach out now to get started.